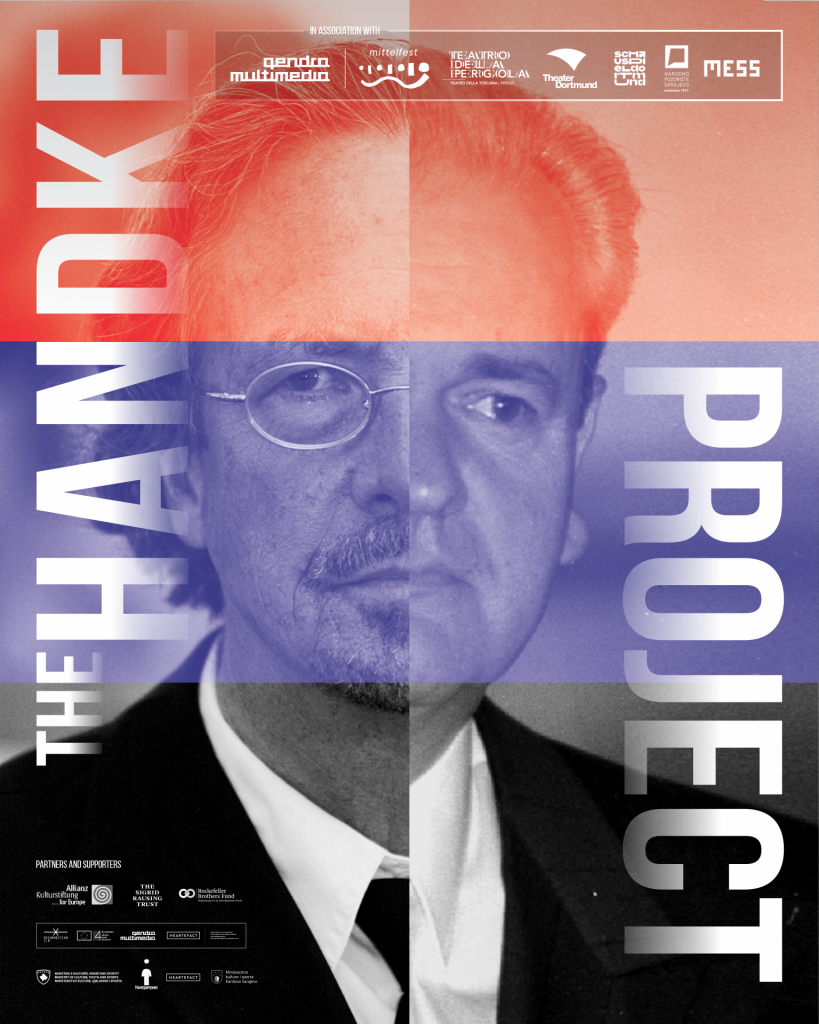

The Handke Project

Qendra Multimedia, Prishtina, Kosovo

Who: Across a cluster article in four parts, all on this page, there are interviews with Kosovo’s writer JETON NEZIRAJ, director BLERTA NEZIRAJ and actor ADRIAN MORINA, plus ‘PETER HANDKE: An Idiot’s Guide to a Useful Idiot’ by Nick Awde

What: Neziraj, Neziraj and Morina discuss their roles in the process of creating a highly charged play that examines freedom of speech versus political consciousness/responsibility, viewed through the Nobel Prize for Literature to Peter Handke – a controversial event due to the Austrian playwright/novelist’s alignment with Serbian nationalism. The play is in English, performed by a pan-European cast in a European co-production by Qendra Multimedia with Italy’s Mittelfest & Teatro della Pergola, Germany’s Theater Dortmund and Bosnia and Herzegovina’s National Theatre of Sarajevo & International Theatre Festival MESS/Scene MESS.

Where & when: European tour June 4-October 30, 2022.

Web: qendra.org

Language note: ‘Qendra’ means ‘centre’ in Albanian and is pronounced something between ‘kyendra’ and ‘chendra’.

IF READ TOGETHER, THIS IS A LONG READ

Jeton Neziraj

Writer, The Handke Project, & artistic director of Qendra Multimedia

Nick Awde: Why Handke?

Jeton Neziraj: We hit war ghosts and monsters of all profiles (including ideological monsters), war criminals, life and city destroyers. In general, we hit those who cause pain, no matter which camp they belong to. And Peter Handke is unfortunately one of them.

We are not interested in Peter Handke the person but rather Peter Handke the phenomenon. In the past – and I am afraid in the future too – we have had and will have good writers who can be arseholes, but for me, and for many others I believe, the ‘Handke problem’ started when he was awarded credible international prizes starting with the International Ibsen Award in Norway and then the Nobel Prize for Literature in Sweden. He was awarded by two stupid Nordic groups, I would say.

Thus Handke interests us not as a writer but as a phenomenon of the European hypocrisy that manages to present fascism (the literary one as well) as ‘freedom of expression’ – and even honours it. In fact Handke is the product of a not-so-glorious time in Europe that we are living in, a time that will bring nothing but new suffering.

The Handke Project is ‘written by Jeton Neziraj’ – how does that work with all the other people involved in its creation?

Croatian-German writer/scholar Alida Bremer is the artistic collaborator and Serbian playwright Biljana Srbljanović is the dramaturg – they have given extremely important advice, recommendations and input, especially during the first phase of writing. For a long time Alida has been at the forefront of all those who have shed light on the stupidity of the Nobel Committee. Both of them have been involved in the work process.

And then there is director Blerta (Neziraj), who was involved from the beginning and she contributed ideas and recommendations during the entire writing process. We also went through an intensive week with the actors where we discussed with everyone involved and they came up with ideas that also served the writing of the play.

We preferred a text that formed a firm blueprint before rehearsals started, to avoid entering a theatre process that might get us lost in discussions and research, especially considering that this would all be done in a language (English) that is not a mother tongue to any of us. A written text as a basis was a necessity!

The play as such is based on extended research and consultation on Handke’s books and writings, documentary materials, interviews, and also the writings of dozens of journalists and writers. An important source was the persistent and enlightening writings of the American journalist Peter Maass.

How did the show happen to end up in English?

Since the show is a co-production with theatres from the Balkans and elsewhere in Europe, the cast is comprised of actors from different countries – so English was the language of compromise.

However, let’s say that ours is a very cute English with a lot of Italian, Slavic, Albanian and French accents and sounds. We simply didn’t want to get lost in the stylisations and diverse sounds of languages, we wanted to get to the core of the matter and with a direct language – one that is understood by all. In other words, a language that most people in Europe understand.

We know that there are more and more audiences now who are able to understand the show directly without the mediation of surtitles. Although we will use surtitles for the Italian and Serbian audiences, in a place like Prishtina the situation is different. Most people here – especially young people – speak and understand English fluently, and young people – up to 80% – are the main theatre audience.

How does touring the show link with your experience of touring your previous big show Balkan Bordello (Bordel Ballkan, directed by Blerta Neziraj)?

In 2019 we were in a longer tour that went to New York’s La MaMa with 55 Shades of Gay. That show’s success paved the path for the next collaboration with La MaMa, Balkan Bordello, which was a challenging yet extraordinary theatre project, firstly because it was the first time we did a transatlantic project but also because La MaMa and Qendra Multimedia were also joined by Atelje 212 Theatre from Belgrade.

Besides the Balkan/New York tour of Balkan Bordello, we are now (2022) preparing it for a tour across five summer festivals in Serbia, North Macedonia and Montenegro, and in the autumn we will come back with a fourth tour of Sarajevo, Podgorica, Zagreb, Belgrade and Prishtina. It’s proved to be a big venture, but a very rare one in this part of the world.

With The Handke Project, after touring Kosovo, North Macedonia and Serbia, in the summer we start with the second stage in Italy, Germany, Bosnia and Herzegovina and beyond. The challenges we will face are yet to be seen, however I can say that at this point we definitely have solid experience of international touring.

But let me also say that in a way we like this theatre nomad life. The stage is our homeland, and that is why we feel good no matter where we perform. For more than ten years, Qendra Multimedia has produced more than 20 shows that have been performed hundreds of times in Europe and America.

It is important to point out that in these productions and co-productions with different theatres, we have always had artists from at least three different countries – like Italy, France, Serbia, Germany, America. Collaboration and exchange with international artists is how we understand theatre today.

Our ideal theatre has different colours, different languages, different sounds, but it transmits the same concerns to every audience, the same dramas and traumas and, finally, the same dreams, because issues, dramas, traumas and dreams are the same for everyone, everywhere – in Kosovo, France, America…

For a poor and isolated country like Kosovo, collaboration and exchange with artists and theatre partners from Europe and the rest of the world is not only an artistic act but also a political one. Yes, a political act – and it must be this way not only for us in Kosovo. In these times when we are witnessing rising xenophobia, racism, nationalism and authoritarianism across Europe, when extreme right-wing and populist movements are expanding everywhere, inter-European cultural exchange and collaboration is a political act.

Was it challenging to set up the tour for The Handke Project?

Preparation took around two years. At first, Berlin’s Gorki Theatre was involved, but communication with them got difficult over time and we simply went on to find other partners who were interested and more committed.

Now I am happy that we have credible theatres and theatre institutions involved as co-producers, including Mittelfest and Teatro della Pergola from Italy, Theater Dortmund from Germany, and National Theatre Sarajevo, as well as the International Theatre Festival Scene MESS from Bosnia and Herzegovina. By joining us in the project, these theatres and festivals have shown courage – because courage is needed for such political projects, because the questions raised are difficult and often uncomfortable and they take us out of the comfort zone of normal theatre routine.

How does the show reflect Kosovan theatre and culture?

Since 2008, when Kosovo was declared an independent state, theatre has been at the forefront of some of the most important societal and political debates. Importantly, as I mentioned, the audience here is mainly young – around 80% are below 40 years old.

Theatre creatives in Kosovo work with what they have in their disposal. First and foremost, they use the actor’s potential and original stories, which is a sort of origin-oriented theatre where the topics are mainly political, tackling local Kosovo politics as well as European ones.

Kosovo theatre portrays these topics with a lot of humour, and often with a lack of political correctness. Though I cannot quite call it the ‘Kosovo New Wave’, good things have started to happen over these past years.

At Qendra Multimedia, we started the Kosovo Theatre Showcase, an annual platform where we showcase theatre productions from Kosovo and the region to an audience of European festival programmers and journalists.

These movements can be seen as tiny steps, but in fact they are important for a theatre scene that was destroyed by the Kosovo War and which had little power to recover for a long time, while also being the most isolated theatre scene in Europe!

And it keeps being isolated. Kosovars are the only people in Europe who cannot move anywhere without visas and this is devastating for theatre enthusiasm. This is why The Handke Project is part of this new theatre spirit in Kosovo, our new tradition in-the-making, theatre that carries enthusiasm, passion and courage within.

How do you think audiences will react across the different countries you’re touring?

That’s difficult to say at this point. What I know for sure is that nationalists in Serbia will not be happy at all and that police presence will be necessary during our shows at BITEF (Belgrade International Theatre Festival).

Police protection for shows from Kosovo in Serbia is nothing new, but there are more reasons this time. A friend of mine, an actor from Serbia, was telling me that touching upon any of the Serbian saints in Serbia might be forgiveable, but they are ready to take your eyes out if you touch Peter Handke.

It already looks like there is some truth in all that. During the production process we lost three actors who were from Serbia. They had committed to being part of the production at the beginning, but as soon as they read parts of the text when it was being written, they withdrew for various reasons but what they were all basically saying is that this is ‘a sensitive topic’. Of course that reaction of theirs served me during the writing process, and now the show has a character: The Serbian Actor Who Gives Up the Show.

How important is Qendra Multimedia to your work?

Qendra and I have grown together. As much as I bear the credit for creating its physiognomy, Qendra bears the credit for creating me and my profile as a playwright. The shows produced by Qendra Multimedia are critical, direct and take up ‘under the carpet’ topics and issues that are considered taboo in Kosovo’s society and politics. This is the freedom that I have always strived for – and now it’s there, a small oasis but it is there, it is tangible.

Qendra grew up and developed together with the new state of Kosovo, sometimes teasing it but mostly loving it and working with the aim for Kosovo to improve and grow into a normal country.

We are now based at the ODA Theatre (Teatri ODA), a basement-like venue in the heart of Prishtina, and even though we have a new government with more liberal and theatre-loving people, we still try to keep our distance because we believe this is healthier for our work and the audience itself.

Blerta Neziraj

Director, The Handke Project, & project coordinator/director of Qendra Multimedia

Nick Awde: Did you start working on the project at its genesis, or did you wait until the writing was complete?

Blerta Neziraj: I already had a few images, ideas and views about certain scenes and a general feel for how the show would look long before the text was ready. In other words, I had a few first directorial impressions that were part of my directorial ‘alarm’ which, once switched on, always remains active until the show is over. Of course once the text came, everything got easier. But not that easy! Because this is an intense theatre text full of references, full of implications, irony and sarcasm – which is typical for Jeton (Neziraj, writer).

What is the thinking behind an international ensemble, and how does it work not only in terms of the different languages and techniques they bring to the table but also their cultural/political filters?

Part of the challenge of the work process here is communication in a language (English) that is secondary or even tertiary for us, and for a project like this, it is an even bigger challenge. Oftentimes we might not manage to communicate to each other what we want, but we try our best and the linguistic and other barriers are tiny in comparison to the benefits, which are mostly artistic in nature.

Because our artists come from different countries, they have different views and expectations from theatre, they have different approaches and training. The process of merging these cultural and professional experiences makes a show diverse, multicoloured, with a very different energy and spirit.

The director in this case becomes like an alchemist harmonising and merging not only the voices and movements of actors and arranging them on stage, but also harmonising and merging between each other’s cultures, experiences and artistic differences.

What are we to think when we see The Handke Project?

I would like the audience to leave with good impressions of the show, not necessarily to agree with what we say on stage but to at least start thinking about it. Of course, if the audience leaves irritated at the stupidities of Peter Handke and the Nobel Committee, that would be ideal. But they can also leaves irritated at our approach.

I would absolutely not like it if the audience leaves the show in the way they would after watching an entertaining comedy. I would not want them to leave relaxed and enthusiastic for the ‘perfect world in which we are living’.

Was the idea always to take the production abroad?

Yes. The show was conceived that way from the beginning, as a show that tours internationally. This is why we hired actors from various countries and decided on English as the show’s language. We have produced shows of an international character before, and they have been conceived in the same way from the start, from choice of subject to selection of the cast and the way they are put on stage, everything conceived for international touring.

What challenges have there been in bringing The Handke Project to life?

The list is long. We always have less time than we need, and unanticipated things happen all the time. This or that collaborator gets sick, this or that actor has family issues, this or that kind of light cannot be found, there are no stores for masks, you cannot order this or that video-projector because you cannot make international online orders from Kosovo… Everything of this nature that can frustrate you.

And of course it was frustrating during the process that Serbian actors whom we hired decided to leave the project because they considered it to be a sensitive topic. Unfortunately, the rehearsal process is not always that entertaining and before arriving at the finish line, everyone’s stress levels reach a peak…

How does the production reflect Kosovo theatre and culture?

I think this is yet another show that manages to show the energy, pulse, enthusiasm and will that has been dominating our theatre scene for a few years now. We are inspired by the local dynamics but we bring a universal approach and aesthetics, open and accessible to all.

How do you think audiences will react, country by country?

The audience can surprise which is why I have given up such presumptions. I simply try to do my work the best way I can and know, and then that work is subject to the audience’s will.

From all the work that Qendra Multimedia has produced up to this point, we know the way how our direct and political topics provoke extreme reactions: from enthusiasm and euphoria on one hand to anger and rage on the other. All reactions are legitimate so long as they are not violent.

How important is Qendra Multimedia’s Kosovo Theatre Showcase to your work?

The Showcase is a good opportunity for us to present our country’s productions. Thanks to it, for example, my show a.y.l.a.n, produced by the City Theater of Gjilan, was invited to Poland’s Kontrapunkt festival (in Szczecin) and won the main prize there. Before that, the City Theater had never travelled to a festival outside the region.

At the Showcase, we not only get to present our work but we also have the chance to meet theatre creatives, promoters and journalists from other parts of the world, because this is something we are still missing in Kosovo – contacts and the exchange of experiences.

Adrian Morina

Actor, The Handke Project

Nick Awde: Does being an actor in Kosovo bring the idea that all cultural acts are political?

Adrian Morina: Being an actor or an artist does not necessarily mean that every work you do or enterprise you lead should have a political character. In Kosovo there are many artists and actors whose work is oriented more towards aesthetics, but for me personally I have more interest in political theatre and politics, especially because we live in Kosovo where politics determine a big part of our everyday lives and I believe that humans are political beings primarily.

That’s why wherever I can contribute and intervene in politics or whatever determines our everyday lives, I feel it is not one my artistic obligation but also my civic duty to address the issues that directly affect us. For me this is why art is there, why theatre exists. This is why theatre was born to begin with. So I am always looking to be a part of productions and groups of artists who create a strong and powerful opposition to systems not only in Kosovo but wherever they are around the world.

Had you worked with Qendra Multimedia before?

I have worked with the company for a long time, and I have known Jeton for more than 20 years. My first play with Qendra Multimedia was Yue Madeleine Yue (musical tragicomedy about a Roma family forcedly expelled from Germany to Kosovo), which must have been 12 years ago.

That was my first engagement with Qendra Multimedia and that that’s when I fell in love with the company, because the play that we worked on gave the Roma community. The artists came from different nationalities and we worked to give a voice to this marginalised community that’s very little heard in Kosovo – just as in other countries too.

We have worked on many theatre projects since then and participated in many festivals. It has given me the chance to work with Jeton (Neziraj, writer), Blerta (Neziraj, director) and other collaborators on projects like The Demolition of the Eiffel Tower (Shembja e kulles se Ajfelit), One Flew Over the Kosovo Theatre (Fluturimi mbi Teatrin e Kosovës), A play with four actors and some pigs and some cows and some horses and a prime minister and a milk cow and some local and international inspectors (set in the ‘Tony Blair Slaughterhouse in Prishtina’), right up to our latest project The Handke Project.

Qendra Multimedia is a kind of symbol of resistance against injustice, not only in our country of course. It is a powerful and strong artistic voice shaking the foundations of all systems.

How does The Handke Project fit with your other work?

I am also a resident actor at the National Theatre of Kosovo, where I work with a diverse repertory of mainly classical shows that tackle a range of topics. In my career there I have worked with top directors from the Balkans and wider Southeast Europe, including Slobodan Unkovski, Vladimir Milcin, Dino Mustafić and András Urbán. I have also worked with theatre directors from Kosovo such as Altin Basha and Ilir Bokshi.

The Handke Project is the kind of theatre I love working on. No matter how many times I have the urge to go back to the classical theatre that we were all taught, I always end up with projects that are closer to my nature as an artist, what I like to call not only political theatre but also engaged theatre.

In this show I think I do almost everything. It is a huge team effort, the kind that Blerta usually does where you don’t just develop a character or do the one job but you do anything necessary to serve the idea of the show and not simply the character that you play.

It is a special pleasure to work with a group of artists who come from different countries and cultures. The play is performed in English and this is a special challenge, a difficult one. I dream of the time when we will be able to insert a chip that will remove language barriers that will let us switch instantly to speak the language of every country where we play.

But it is important for the actor to be able to express themselves no matter the language. Though the team speak and read English, we think in our native languages, but everyone has worked together to overcome this challenge.

At the end of the day, everyone knows where we come from and of course the audience will understand us because it is not necessary for us to sound like Americans or Britons. The language of theatre is universal and we should be able to express ourselves through theatre and be understood no matter where we perform the show. If we do not achieve this goal then we will have failed, but with The Handke Project I believe we will communicate clearly with the audience.

How does The Handke Project reflect Kosovo theatre and culture?

The show does not necessarily represent our theatre or general culture. On another level, I do not believe that artists should carry the weight of the entire nation on our shoulders, to claim that we represent Kosovo or that what we do is Kosovo culture or Kosovo theatre or Albanian theatre. Absolutely not.

This is a production that comes from Qendra Multimedia with all its collaborators, none of whom are there by accident. The company has its longterm collaborators precisely because they share the same thoughts and values. The Handke Project is a show that represents a group of people who speak freely, who speak openly, this time more openly than ever, more directly than ever as we speak about Peter Handke and take a position on that.

This is why I need to point out that this is not necessarily the type of theatre that is produced or even liked that much in Kosovo, because here theatre continues to remain mostly within the classical margins, although there are some tendencies that break from this. But in the repertories of Kosovo theatre, it doesn’t happen often that you find political shows, not because people are not courageous – because I do not want to brag and say that we are courageous and doing extraordinary things – but because people in general are not interested in this kind of theatre. We usually have classical shows and various comedies, and I am a part of that as well because I am a resident actor at the National Theatre of Kosovo.

So no, this show does not represent Kosovar culture. It exclusively represents a particular group of people who have gathered around an idea and who have pushed forward a production that we hope people will appreciate.

How do you think audiences will react, country by country?

Let’s hope that the reactions will be different, because it would not be normal if we only have applause at the end of every performance no matter which country it is. Let’s hope that each audience will react differently, and that is what I expect will happen. It is almost impossible to think you will get the same reaction in Kosovo or Germany or elsewhere, because the show speaks so openly and directly about its subject. In fact it is a real possibility that we will not be allowed to play in certain theatres.

It has already been an interesting journey so far, with some actors who joined at the beginning and then gave up the project at certain points and are no longer part of it. Their excuse was not just that they didn’t want to be part of The Handke Project or that they were not courageous enough to be part of it – because let me say it again we are not doing anything extraordinary – but they also left the project because of the discussions we all had in the first phase when the text was still being written.

I completely understand that. In many European theatres it is impossible to discuss a subject like Peter Handke, for example, without having an Austrian perspective or having an Austrian in the project who can bring a totally different perspective. Certainly in our show we discuss many figures of our time and also historical ones without having representation from the countries we’re speaking about, and of course I do not expect the show to be received the same way in Prishtina and in Belgrade. It might be that we won’t be able to perform in Belgrade at all, just starting from the poster itself (a collage of the faces of Handke and Serb leader Slobodan Milošević), which can be seen as highly provocative.

In the UK’s theatres today and everywhere else there is a huge debate on what artists can and cannot do or say on stage and who they can work with depending on the project. In our case we have not made these choices of compromise to include those we talk about at any cost. At the end of the day, this is the position of a particular group of artists who have come to work together convinced of the worth of the work we are doing, with the deepest honesty.

So I think audience reactions will be totally different, and not because the show opens up debate or discussion, or simply provokes, because that’s not the goal here – nor is it my personal goal to provoke anyone or do something just for the sake of opening up debate – because as far as that goes, we can achieve that with far easier actions. If we went running naked down the streets of Prishtina, that would open a debate.

With all the background that Jeton and Blerta and the artists and collaborators have brought to The Handke Project, the way we have approached this project means that reactions will not be the same. I am curious to see how people will react, and I am certain they will not be the same as in Prishtina.

How important are Qendra Multimedia and its Kosovo Theatre Showcase to the work of Kosovar performers and creatives?

The Kosovo Theatre Showcase is a great opportunity for local artists and for audiences in Kosovo to see the productions and the work of regional and international artists, because our communication with the outside world, especially to share the works produced in Kosovo, is difficult, full of bureaucratic procedures, visas and documentations, applications and 100,000 problems that pop up along the road.

The Showcase is therefore a great opportunity for us to show our work, produced in Kosovo, in front of people who have come here to see them, be they actors, artists, directors, producers or others from the field of theatre or journalists.

Of course, Qendra Multimedia is doing great work. Imagine, we still do not have an international theatre festival in Kosovo. We had one until 2005 but it stopped operating. The opportunities for people to see work by internationally renowned artists is very limited while sending our works abroad is also difficult.

This is why the Kosovo Theatre Showcase is a good opportunity for us to get to know each other and see each other’s works, and of course, if we like each other’s works then there is a great chance to exchange knowledge, exchange works between Kosovo and other countries. I think that The Handke Project itself is a product of bridges built during the Kosovo Theatre Showcase. It is a great opportunity for those engaged in theatre and who live for theatre.

How are things going currently for performers and creatives in Kosovo in relation to solving the challenges left by the pandemic?

I come from a country, a territory, a nation that is used to adaptation and has adapted to every circumstance. Let’s not forget that we went through a period of ‘light’ occupation up to the 90s and then real occupation during the 90s and the war. We survived all that, here we are today, here I am giving you an interview…

Of course, we tried to behave during the pandemic as if everything was normal, and we were lucky that during the times when other countries were not allowed to do theatre, we somehow insisted.

During that time I was acting artistic director of the National Theatre of Kosovo and I remember how right before the pandemic (in 2020) we started a project, Zgjimi I Pranverës, or Spring Awakening, which was then postponed for so long that we only managed to open in June, even though we were already in summer and no longer in spring. Our enthusiasm helped us finish the project and then we continued with other works.

Let me say again that we were lucky in comparison to other countries because we were given more time to work – this is the most important thing for an artist. As far as other things go, such as financial consequences, these have been irreversible, especially for artists on the independent scene where the pandemic was a real catastrophe because for a long time there were very limited funds allocated to them.

We don’t have a social security system to be proud of, one that would make it possible for people to survive without working, and in all this mess, the artists who were in full-time jobs – like I was and am at the National Theatre of Kosovo – felt ashamed because we were still generating income even without working but this didn’t apply to the independent artists.

Of course we are still to realise all of the consequences of the pandemic. Some are very evident today, such as the difficulty in bringing audiences back to the theatre, but we work every day, giving everything we can in order to return to the ‘old’ normal – or the ‘new’ normal, I don’t know exactly which.

The pandemic will most probably last for some more time, but one thing is clear: theatre existed before the pandemic, before the war, before all wars, before civilisations, and I don’t think there is any force that can stop it.

A few days ago I spent time with a director who has worked for a long time in Ukraine and continues to work there – because theatre in Ukraine, despite the war, is still functioning. During the war in Kosovo theatre functioned, as well as in Bosnia, where we have friends who tell us about the time when they did theatre during the war there. This shows why theatre was here before us and will be here forever.

Peter Handke: An Idiot’s Guide to a Useful Idiot

by Nick Awde

There’s a huge amount of knowledge about German-language theatre (and literature) that never reaches the UK’s shores – which is a shame given the vibrancy/heritage of things like the Berlin theatre scene, state powerhouses like Thalia and the festival circuit that sprawls over Germany, Austria and Switzerland.

The gulf exists for good reasons: the UK is overflowing with homegrown theatre; German/Austrian/Swiss funding (like most other nations in Europe) skips touring the UK; exportable German productions are often too large-scale or technically complex to tour here; the lack of meaningful connection in the UK with German-speaking theatres; the UK’s lack of knowledge of German language or related culture – and so on.

UK audiences tend to catch German-language stuff via a West End adaptation – most recently, erm… or a National Theatre/Barbican season that includes a show or director (not all are German/Austrian-born) like, erm… Well, at least you can catch the odd Austrian or Swiss show at the Edinburgh International Festival or something locally produced with an imported German-speaking director at the helm. And on the fringe you’ll spot the occasional Spring Awakening – and perennially a Schiller (because the directors did it at uni).

Little of this of course is accessible to audiences outside of the London/Edinburgh/Manchester orbit, and it’s nowhere near enough to be representative of how things are done in the German-speaking world.

Another type of barrier is raised by the context-free hype of German-language theatre thanks to high-profile British arts journalists, where they pop off to Theatertreffen in Berlin for a boozy long weekend then land back at Luton airport early Monday morning tweeting about the shows they’ve seen. Oblivious to what they have actually seen and heard (and, I suspect, not speaking a word of German) they’ll own the shows by presenting them as ‘European-so-it-must-be-good’ to us cultural dunces in Britland and namechecking the latest hot Berlin director we’ve never heard of.

Meanwhile our academics dripfeed us with whatever tat they’re gatekeeping for their research papers, ultimately tunnelling theatre audiences into context-free performances of texts disingenuously described as ‘difficult’ (i.e. not very good). So rather than informing us, all of this conspires to create a blind spot in the UK for the appreciation and understanding of German-language theatre, be it old or new.

One of its mainstream features that we could learn a lot from is the active bonding between directors and writers to shape a flexible and powerful storytelling narrative that is very society-based and often political with a small ‘p’, involving anything from trad ensembles to hi-tech staging and which for decades has been a major influence on the rest of Europe and America.

Which handily brings us to Peter Handke…

Born during in Austria during the Second World War to a struggling family (as was almost everyone at the time), he started writing plays and novels in the 60s where he was seen as avant-garde (as was almost everyone at the time), helped by being part of a cultural generation (as was almost everyone at the time). Novels like A Moment of True Feeling (Die Stunde der wahren Empfindung) and The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick (Die Angst des Tormanns beim Elfmeter) built on early plays like Kaspar and Offending the Audience and Self-Accusation (Publikumsbeschimpfung und andere Sprechstücke), his prose evolving into streams of stark words that meander like a walking diary through his life.

Handke soon earned a reputation for pushing the language of narrative into the meaning of life, and by the 80s he had started to climb the giants of literature charts, well on his way to international award-topper status by the 90s. And yet, with the exception of his scriptwork on the magnificent Wings of Desire (Der Himmel über Berlin, 1987) – Wim Wenders’ 1987 film that, tellingly, was co-written with Wenders and Richard Reitinger (and a film, not a book or play) – I honestly can’t see anything to convince that Handke’s works hold a lasting message for us Brits, for the simple fact that it’s not us that he’s writing for.

It’s not a question of linguistic or cultural barriers (most of his work is in English translation) but the fact that Handke charts a river only the Germans and Austrians swim in (I regret committing a gross conflation here). Even if he’s walking us through a life in Paris (A Moment of True Feeling) or communist Yugoslavia (Repetition/Die Wiederholung), the worldview is Austrian, the pinhole minutely Austrian, minutely Handke.

So if I’m again to be honest, his themes appear elusive to us, his wordsmithery one-dimensional – the basic gimmick in his novels being that you have to be at his side as he navelgazes his way through narrow slices of societal life. And while his plays are populated with intriguing characters, their dialogue has the depth of a take-away menu and ultimately takes you nowhere. I do need to insert the caveat that my German isn’t brilliant and the English translations I’ve seen are bafflingly lacklustre and really don’t seem representative.

To many many many others, of course, his work speaks volumes – indeed his Nobel Prize (more of which later) was awarded “for an influential work that with linguistic ingenuity has explored the periphery and the specificity of human experience”. But for me there are tons of writers of Handke’s generation who are as nationbound if not more so, and yet are far more accessible – I give you Werner Schwab, a wholly culturally absorbed playwright who, on paper, seems far more impenetrable than his fellow Austrian.

But Handke needs to be on our radar. He needs to be be important to us if not artistically then because of his status and high regard which has spotlighted the unquestioning acceptance in his works and actions for the Serbian nationalism that fuelled the deadly conflicts of the break-up of communist Yugoslavia over 1991-2001.

The spark was an article he wrote in 1996 for the German newspaper Suddeutsche Zeitung about a trip he made to Serbia, portraying Serbs as victims of the Yugoslav Wars. It was published just one year after the massacre of Bosnian men and boys in Srebrenica by the Serbs. When NATO bombed Yugoslavia to force Serbian forces to withdraw from Kosovo, Handke again rose to the defence. He has written and said loads more stuff in the same vein.

Self-destructive identification with foreign causes happens everywhere, and I need to stress that each case needs contextualising before passing judgement – we have only look at the complex intertwined history of the Balkans, which requires serious unpicking, and its relationship to Handke’s own family background. However, in delving into his mother’s Slovenian background/neighbouring Yugoslavia, Handke blithely ignored any pretence at contextualising and found a new family not in Yugoslavians but Serbian nationalists and a new BFF in Serb leader and war criminal Slobodan Milošević.

Handke’s response to the criticism he faced for these one-sided sympathies (and spare me the whataboutism) was to roll out unconvincing ‘us and them’ arguments about Serbs being misrepresented as aggressors. Yes he backtracked a number of times and handed over award money to non-Serbs, yet he continued to hobnob with Milošević who lapped him up. Of course the Serbian leader did, because Handke was his useful idiot.

Having spent more of my life working on ethnoconflict than theatre, I encounter useful idiots with depressing frequency and Handke is just one of endless stream who embrace unsafe regimes and causes and get embraced in return. They’re feted and feasted, their opinions sought and paraded on TV as justification of how the ‘real people’ in the West think (‘speaking the truth’ features a lot), providing apologist optics that also make them intractably complicit. They can never undo this.

I doubt Handke has ever sought context, instead he argues that his ‘perceived’ political stance cannot be connected to his literary work – but though he’s too thick to be a fully fledged genocide denier, it doesn’t dilute his influence on those who are. Words count. This general absence of clarity on Planet Handke provoked an undignified scramble by his peers either to disassociate themselves from his denial (mainly international liggers like Susan Sontag and Salman Rushdie) or to affirm his claim that art and politics are not connected (lots of Europeans).

The latter in many ways have won. As proof that that Europe’s intelligentsia have closed ranks in support, Handke’s validation came in the shape of the 2014 Ibsen International Award (in Oslo with a cash prize of NOK2.5 million / GBP200,000, theatre’s biggest and seen as the ‘Nobel Prize for Theatre’) followed by the 2019 Nobel Prize for Literature (cash prize of SEK10million / GBP800,000). Now, freelance journalists in the UK earn not a lot (it’s getting astoundingly worse each year) and to match that sort of cash in terms of day rates, I’d need a hundred years or so of solid graft. Writing for the dark side may have its drawbacks, but I’m sorely tempted.

Protests and denunciations ensued of course but failed to dent the openly defiant award ceremonies. In Oslo, I (as observer) was among the angry crowds protesting outside the National Theatre when Handke arrived for his Ibsen. He turned for a moment at the foyer entrance to stare stony-faced at all those in the plaza, many from the Balkans, but his composure dropped to a scowl before marching into the theatre where he accepted his prize and delivered a rambling speech about not a lot.

We stayed in our seats to watch his Immer noch Sturm, an unexpectedly hollow large-ensemble version from Thalia Theater and directed by the late Dimiter Gotscheff (a German whose own communist-era connections included being Bulgarian-born and working with East German Heiner Müller).

It was revealing that Handke had no answers. Okay, no answers for a hostile crowd is understandable, but surely he had something up his sleeve as he stood onstage before his peers or something to help make sense of Thalia’s voices. All I witnessed was a waspish little man, irked that his greatness was not deemed sufficient to silence his critics, displeased that the great unwashed had dared to challenge that greatness.

Did I want to interview him? No. Do I want to sit over a pint in the pub with him? No. Am I being unreasonable, uninformed and refusing to see both sides of the argument? Fuck no.

Our collective cultural/academic landscapes are presently littered with very visible useful idiots, self-absorbed apologists and deniers. Across the UK and Europe we are becoming more aware of the educated classes who tell us that Russian culture is a universal saviour and not a colonial weapon, who tell us that peace and understanding will come if we accept that Russian art is greater than the inconvenient reality of politics, war and genocide. The likes of Russian cultural greats like Pushkin, Tchaikovsky and the Bolshoi hold the healing flame that will enable the world’s peoples to live together side by side in harmony. Compromises (one-sided) have to be made. Anything else is Russophobia.

Russia’s war on Ukraine is therefore forcing us to take a good look at these useful idiots and to reassess their influence on our societies in the light of their complicity, starting with Russia’s appropriation, weaponisation, erasure and retcon of culture on an industrial scale never seen before in history.

Like so many useful idiots, Peter Handke is a lazy apologist who doesn’t do the research. The continued adoration from his adopted community, who still self-present as victim, is all the affirmation he needs, and it absolves him of responsibility. Yes he has redistributed prize money, yes he has mumbled stuff about the other side being harmed too, but by pushing the hallowed tenets of ‘freedom of speech/expression’, by placing art above politics, by pushing the unifying power of culture, Handke wilfully ignores the systemic onslaught by Serbian nationalism on Kosovan, Bosnian and other Balkan culture and language, key to the attacks on their political survival, no different to the historic, present and projected Russian attacks on Ukrainian culture, language and statehood.

We can’t pretend that he is not there, we can’t unsay what he has said or undo his visible status, so to award Handke the Ibsen and Nobel for his art is to reward his politics, his support for the aggressor.

This is the spark for Qendra Multimedia’s latest show The Handke Project, which uses the awards controversy as a jumping-off point “to explore how art is appreciated and promoted when it crosses the boundaries of basic decency, humanism or ethics”.

Based in Kosovo’s capital Prishtina, Qendra Multimedia’s writer Jeton Neziraj and director Blerta Neziraj not only have an opinion to share with us about the ‘Handke phenomenon’ but they also have the lived experience to back it up. Their country after all is a new state whose official recognition won’t stop being an international hot potato thanks to Serbia and Russia declaring its very existence to be illegitimate. And we should note how the fact of having an aggressive destabilising larger neighbour creates the sad irony that, at the time of writing this, Ukraine has not been able to formally recognise Kosovo’s declaration of independence in 2008 – which is also the case for all the other former Soviet republics bar the EU-member Baltics.

The Handke Project is timely in showcasing his Nobel Prize as a launchpad to get us thinking how no one should be exempt from being accountable for their actions and words, how as we’ve seen again and again any defence of ‘freedom of speech’ risks falling into the French/American construct that equates it with ‘freedom to speak without responsibility’ and ‘freedom to hate’ (it’s significant that the writer has lived in Paris since 1990), how seeking to give both sides equal weight isn’t democracy when one side clearly isn’t democratic. Dangerous waters sure, but ones we have been forced to plunge into.

And so, on our behalf, Kosovo’s The Handke Project stands up for the freedom to question why we tolerate our useful idiots and enablers (today they number national leaders like France’s Emmanuel Macron, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, the UK’s own Boris Johnson) and finding an answer to the rising wave of well-connected intellectuals who are now activating against ‘anti-Handke propaganda’. Because theatre can do that.