Kosovo Albania Theatre Showcase 2024 – the Tirana interviews

by Nick Awde

Who: Forming a ‘cluster feature’ are street-style interviews with Jeton Neziraj, Altin Basha, Endri Çela, Ema Andrea, Elisabeth Schuster, Ivanka Apostolova Baskar, Steven Leigh Morris, Aktina Stathaki and Aurela Kadriu

What: Curated by Qendra Multimedia, Kosovo Theatre Showcase happens each year in Prishtina and other cities of Kosovo. 2024 sees the 8th edition transplanted to Albania and co-produced by Qendra, the National Theatre of Albania and the National Experimental Theatre Kujtim Spahivogli

Where: Tirana’s ArTurbina – a former hydro-turbine laboratory during Communist times – and the Tulla Culture Centre

When: October/November 2024

IG: arturbina_official | FB: tullacenter | FB: tkeksperimental

qendra.org/kosovo-theatre-showcase | teatrikombetar.gov.al

If read together, this is a long read… and do read Natasha Tripney’s artistic overview of the festival at natashatripney.substack.com

1. Jeton Neziraj on promotions

Artistic director of the Kosovo Albania Theatre Showcase and director of Prishtina’s Qendra Multimedia.

qendra.org

I’ve caught you in the middle of the festival. As the debut edition of the Showcase outside of Kosovo, how’s it working out so far?

We didn’t really know what to expect but we are not encountering that many challenges thanks to our host’s will and curiosity. Logistically it has been far more work than doing the festival in Prishtina, but this is also because this year we have a bigger number of shows than in past editions. In fact, there are two good reasons we decided to move the festival to Tirana this year. One is practical and has to do with the fact that at the moment we lack venue space in Prishtina, mainly because the National Theatre is still being renovated and there is also a plan for our own theatre at Qendra to be renovated this year, which meant that we didn’t want to risk announcing the showcase in Kosovo and then having to improvise on spaces. The second reason is the idea of coming to new territory and exploring a theatre landscape that isn’t well known outside of Albania and Kosovo. It has proved a good decision because so many people here have come to understand what is going on.

Is this biggest edition for the festival?

Not in the number of shows but definitely in the number of people attending, including the international guests. In Prishtina we were definitely busy with 14 shows in 2022 and a range of different panels. Being here in Tirana has created the possibility for more people to come in contact with the Albanian-language theatre scene which gives it more visibility internationally, and of course that’s the core of a festival like this. It also reflects the way the festival has developed, where a platform designed to promote Kosovo’s theatre to the outside world has also become a platform to connect up the regional Balkan scene.

People keep coming because they realise that it’s a productive place where they can meet each other and promote their work. We have a couple of events that are of promotional nature including the International Theatre Market where people have ten minutes to present their projects and New Plays, New Worlds which presents readings of new contemporary plays. It has become larger than we had thought because our ambitions were limited in the beginning when the first edition in 2018 launched as a Qendra Multimedia showcase. We then started to learn and understand the areas where we needed to focus more and develop.

How does the festival highlight the similarities and differences between the Albania and Kosovo theatre scenes?

Being here really makes you think. For example, when it comes to budget the Kosovo theatre scene has a lot more than our counterpart in Albania – our budget for culture has been increased around 300 per cent and we are all surprised, not really understanding what has gone ‘wrong’! By exploring the Albania scene, we also want to shed a little light on their challenges. I don’t think these will be addressed immediately but the festival is a bit of positive pressure on the authorities here to understand that they should invest little bit more money in theatre.

It’s like a completely different landscape, but remember that for at least 50 years we have had different historical roots. This is not only in relation to Albania but also countries like Serbia, where we have colleagues and theatre-makers who we are in regular contact with. In every edition, for example, we have featured a show from Serbia right up to this year with Heartefact Fund’s How I Learned to Drive. So we are learning to cope with each other, to understand each other, to learn from each other.

2. Altin Basha on coproductions

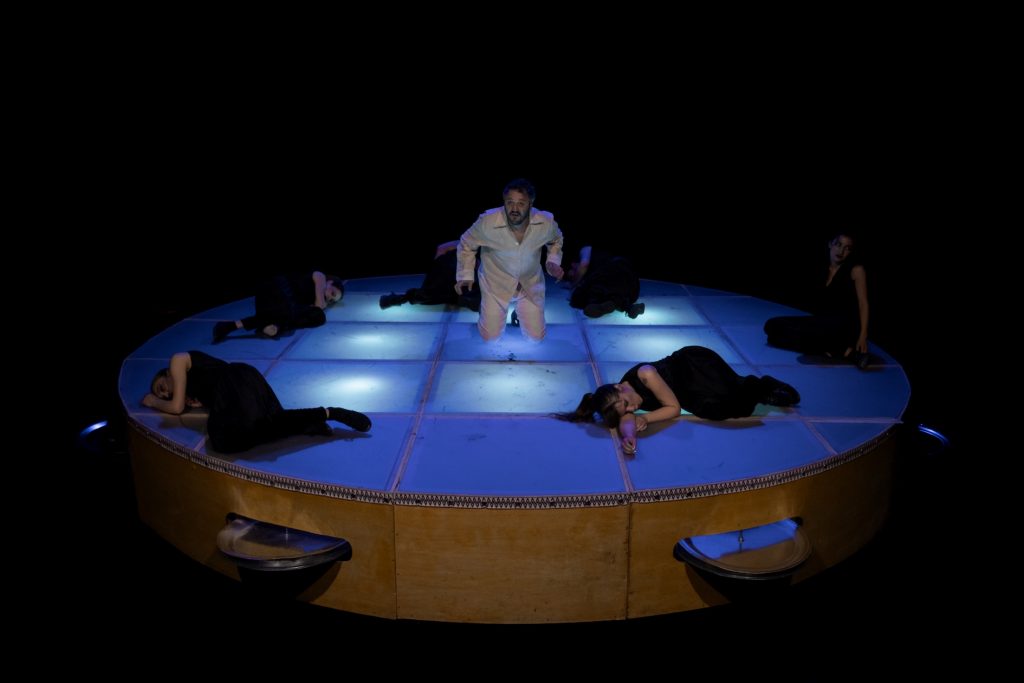

Artistic director of the National Theatre of Albania, who co-produced Faust with Sardegna Teatro in association with Istituto Italiano di Cultura – directed by Davide Iodice and translated into Albanian by Ina Gjonçi from a script based on texts by Goethe, Spies and Marlowe @ ArTurbina.

teatrikombetar.gov.al

How does the National’s production of Faust reflect the Albanian way of producing large-scale works?

This was the premiere that you saw at the festival, a co-production with Italy’s Sardegna Teatro. Davide Iodice created the show in two and a half months – his method was very intensive, he kept rehearsing the show which gave time to the actors to smooth out the whole show. He worked from the beginning directly on stage, which was different for us because our system tends to start with a table-read before going on to movement, then a general rehearsal before the opening night. Instead he took 15 full rehearsals before the opening night – that was good because the actors were very familiar with the show.

So working with a foreign director introduces new practice as well as a new creative vision?

Yes, and we have been doing this regularly since I joined the National Theatre – Davide is now the fourth foreign director who has worked with the company. The productions are successful but what also happens is that it creates a difference in what the audiences are used to seeing on our stages. Faust, for example, is more modern whereas our audiences like it traditional, and it has been challenging for the company itself to get used to working with foreign theatre-makers if only because of the language and cultural barriers.

Faust was Davide’s proposal. He brought his show The Visit in 2023 to the Moisiu National Theatre Festival here in Tirana, where it won awards for best show and best stage design. His co-producers were also here and we discussed the possibility of a new show and also what kind of theatre and themes are done and not done in Albania. Faust is ‘not done’ here, so that was a good opportunity, and of course because it is a classic story there is that kind of dramatic/lyrical theatre that audiences like. So he took the idea and of course he created his own concept, and we didn’t interfere in that process.

Even though the National Theatre doesn’t have a base at the moment, are you able to keep on developing a body of shows?

I’m trying to build up a repertory but it’s difficult. With Faust, we will perform the show until the end of 2024. We will participate in the Moisiu festival in Prishtina – it happens in Kosovo this year because it rotates. [After this interview the festival in late November was cancelled due to a strike by the Union of Artists of the National Theatre in Kosovo.] Then we’ll tour around Albania, which is an important moment for the National Theatre. We will offer the production to other festivals and then we hope to take it to Italy where our co-producers are and perform there.

A festival can be a good place to premiere a production, especially an international co-production.

It has been a good opportunity to use the festival to introduce the show to an international audience and this is possibly the first time we have used surtitles in the National Theatre. This means we can now perform Faust and other productions for tourists and other visitors, because an increasing number of people come to see Albania each year, and with the accessibility of translation, we will have shows to show them.

3. Endri Çela on innovations

Director of Flower Sajza, a multimedia play based on the personal testimonies of survivors of the Tepelena internment camp run by the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania, produced by the National Experimental Theatre of Tirana Kujtim Spahivogli with the support of the Institute of Studies on Crimes and Consequences @ ArTurbina.

FB: tkeksperimental

Is documentary-style theatre a thing in Albania?

It’s new to us. Ema Andrea has created work about the camps and when she introduced her organisation M.A.M. at the Showcase’s International Theatre Market, she mentioned how they have produced things to remind people of the camps. These were not full performances but involved songs or memorial pieces and so they were not fully documentary theatre. So in Flower Sajza you have witnessed something very special that shows what we can do with theatre for Albania.

Was it difficult to put everything in one place for an audience?

For the materials, yes. I took all the interviews that spoke about the internment camps in Communist times as well as everything that the former prisoners have written – at the moment there are around ten books. The House of Leaves [Tirana’s Museum of Secret Surveillance] also helped me through this part of the process. I spent a couple of months reading all this information and selected the elements that I thought would work for a theatre audience, and I was then able to put it all into a dramatic structure.

It is a huge responsibility because I knew that I had to understand the subject matter in depth and choose the most sensitive approach to how to stage this subject while keeping respect for the people whose testimonies we are staging. So we had to make Flower Sajza in such a way that people would not say that it is just entertainment.

How does putting on a show like this work in Albania – does it go into repertory?

It depends on the theatre – and in our case this is a production of the National Experimental Theatre so it depends on them. The premiere was in March this year [2024] when we had one week of four nights, and then there were performances in June in Tirana and other parts of the country.

The audiences have congratulated us for putting something like this for the first time on the stage. And then a couple of older people have phoned me to say they suffered in the camps and wanted to show their support for Flower Sajza even though they didn’t see it because they are abroad. The adverts for the show don’t travel so far, but they found out because of interviews we have done on television about it. So far, the play has affected audiences deeply here and we are working to put the witness of Albania’s camp survivors in front of new audiences in the future.

4. Elisabeth Schuster on horizons

Co-coordinator of the German-speaking committee and member of Eurodram, aka the European Network of Drama in Translation, a network with about 300 members organised and roughly 30 committees.

eurodram.org | German language committee page: eurodram-deutschsprachiges-komitee

What were the aims for Eurodram in Tirana?

The co-ordinators of the various language committees meet once a year for the General Assembly to present their annual selection of new theatre texts, to discuss international collaborations and to get to know each other better. The aim of Eurodram is to translate new theatre texts from different languages into other languages, to stage the local texts in other countries and the foreign-language plays at home, and to circulate and publicise them as much as possible in Europe.

During the Kosovo Albania Theatre Showcase, we have had this wonderful opportunity to present our voluntary and idealistic work, explain the annual competition and the text selection, point out opportunities for translation funds and make valuable contacts with international theatre makers in order to win them over to our cause. Because firstly, we need more publicity for our work and secondly, we are looking for partners and formats to present these new texts and to finance our work.

In addition to presenting our own work at the festival, we were able to get to know contemporary and classical theatre texts in Albanian, Serbian and Greek, watch productions with surtitles and experience a cultural sphere and its themes that are almost unknown in our home countries. By doing so, we ourselves became agents for these new texts, theatre-makers and themes, which we can now present for discussion in our own languages.

How did choosing Tirana happen?

Fortunately, we were invited to Tirana in November 2024 by Jeton Neziraj, who is the coordinator of our Albanian committee as well as the artistic director of the Showcase, to hold our General Assembly during the Kosovo Albania Theatre Showcase and to present our work at the festival. We were very pleased because we were able to meet within Eurodram and promote our work to international theatre makers at the same time. It would be fantastic if we could meet each year during a showcase and present our work and see examples of contemporary theatre of the region in order to broaden our horizons and spread the word.

How was Eurodram received here both from members and from the rest of the theatre community?

There are always a lot of questions about our competition, which alternates between promoting original texts one year and translations into the language of the respective committee the next. On our panel we had the chance to explain our procedures so that authors, translators and theatre makers know how to apply and what opportunities open to them through the competition. It’s not just for young playwrights but also for established ones to get international exposure. We were able to point out that our Eurodram website also functions as a database for authors, translators and translation grants. As our work is almost entirely voluntary, there is of course a lot of room for improvement in the design and processing of the data, which was also pointed out by other theatre makers.

It is very encouraging that we were able to motivate theatre people from different languages during the festival to join or support one of the 30 committees. This is extremely important for our work, because we have to keep feeding our network with new committed people in order to guarantee the continuous work of Eurodram and the networking between the various European theatre scenes.

In what way does the Showcase in Tirana help the organisation on its journey?

Festivals are the perfect place to get to know new theatre texts and to do networking. I hope that we will be able to present our work for Eurodram regularly at theatre festivals in different European countries in the future. The Showcase, with its many different formats, panels and workshops in addition to the theatre performances, has been an excellent place for connecting.

What is your own personal takeaway?

It was a great pleasure for me to see two of Jeton Neziraj’s plays on stage. In Six against Turkey, directed by Blerta Neziraj, and The Internationals, directed by Aktina Stathaki, the comedy and political dimensions worked perfectly together. The presentation of scenes from the Post, Post Communist Baby workshop with Mark Ravenhill was also enlightening and showed a new generation of young Albanian-speaking female authors who write in a self-confidently feminine and funny way and have a desire to deal with their own past.

5. Ema Andrea on interventions

Actress, director and producer, and founder of M.A.M. (Multidisciplinary Arts Movement), founded in 2013 by Albanian artists to assist and encourage innovation, experimentation and potential in the arts.

multidisciplinaryarts.org

Your presentation of M.A.M. at the International Theatre Market highlighted the challenges of funding and presenting work in Albania, while it also showed how the country is a unique case in Europe, where the lack of investment in culture during Communism times is challenging because there isn’t much legacy to adapt to a modern model.

It is trying to change the old ways without having the correct tools to do it. And it has been difficult to find the knowledge here to develop new ways to build up theatre while trying not to destroy the established way of doing things. It is more difficult to change structural and institutional mentalities than to start from the beginning.

In Albania my generation made art because we believed in it – but because of the way Albania was in Communist times there was nothing to prepare us to take the necessary next steps when Communism actually ended. We were naive as a generation about understanding the relationship between artists and policy and how much you have to fight in the opposite direction just to produce art. We didn’t know this and we have had to learn step by step how to work, and we are still resisting in order to give the younger generations hope.

How is M.A.M. helping this to happen?

We have built up M.A.M. hoping that it will make the process easier for young people to progress in the arts, but it’s always the same struggle in Albania because the more you achieve, the more difficult it becomes. We want people to take inspiration from our mission to show what society needs to talk about and the examples that we need to give to the younger generation about the purpose of art. All of this is difficult because money is becoming a god, which makes it so easy now for artists to be ignored.

But even if you work independently, money is important.

Of course. So we need to see our cultural institutions become stronger financially as well as in the quality of what they produce. Art needs to be part of the life of Albania and not just entertainment, it can’t be just having a good time. So I am trying to mix art into social activities for young people because that makes people talk. It’s sometimes easier to talk about the character that you see on stage than to talk about your own problems directly. So theatre can help to build up a new way of communication – because at the moment we have this taboo in Albania of talking in public about our problems.

Festivals like the Showcase help because they are a point of meeting and talking about international culture and alternative culture with relation to Albania. In June this year [2024] M.A.M. produced our own festival, Mediums [with performances from Greece, Italy, Turkey and Sarajevo]. This first edition was successful but I’m afraid for its continuity if I don’t find international partners. Even though we presented the performances in public spaces, it showed that you still struggle to produce at a low cost.

What was the secret to the success of Mediums?

Young people. They believed in it. And they created a lot of publicity and they came curious to see the shows and to talk about them. But when we launched Mediums [M.A.M. also produced 2016’s My Name Is Balkan, featuring readings of contemporary Balkan plays], we were worried that a minister would come and try to move us into a safe space, one that the official policy creates for you. In Albania funding and resources are not easy or possible for independent work because organisations become more and more orientated by Ministry of Culture policy – and it’s perfectly fair to say that they vandalise themselves. We have a history of our long-term festivals closing, even very successful ones, so we also need a change in attitudes.

I was happy to have the opportunity to talk at the Showcase’s International Theatre Market about collaborating with people abroad who have a common interest. If we can do this with Macedonia, Greece, Norway or any other country, it will be easier for us to to share costs in particular. Networking and collaborating are essential, but in the end, as I have pointed out, it is money. It is concerning that all over the world funding is being cut even in countries like Germany. This is dangerous because official policies do not consider art as an important part of civilisation and society. So M.A.M. is here to build up the next generation of citizens who are all forgetting to ask the simplest question: why am I doing this?

And yet eroding the foundations for making art seems to be a worldwide phenomenon nowadays.

Art is a worldwide experience that we all share, it leads our conscience to subjects that we don’t want to face or that society will not allow us to face. We see everywhere that art is ignored and pushed into the corner of society, it puts the artist in the position of begging and this is dangerous for the future. Therefore we need to work together, and we need to resist together.

6. Ivanka Apostolova Baskar on selections

Producer, director, visual dramaturg, editor, translator, lecturer, head of the Macedonian Centre of the International Theatre Institute and writer for The Theatre Times and SEEStage.

Macedonia ITI

What do you think is the secret to Qendra Multimedia making a festival like this work for (almost) everyone in the south of the Balkans, a region with so many challenges?

First of all, festival director Jeton Neziraj and his team are a talented group of fighters who are artists and cultural workers. And then there are the policies of the EU and USA policies that make them positively inclined at the moment towards Kosovo through financial and political support. Given this state of reality, smart artists use it smartly.

Negative selection is a problem in Macedonia, where there is a 90 per cent predominance of the average and sub-average in art, culture, theatre, education… and politics. This is destructive for us. But negative selection is not dominant in Kosovo culture, and for Qendra Multimedia there is this moment of support and showing courage within that support so that the festival, for example, can include Serbian-language productions, which means that democracy in culture is more visible.

In Macedonia, artists who are close to political parties get the good positions and benefits. They are then the voice of political party sophistication. But their voice is opportunistic and they do not solve the challenges that affect all of us in the cultural community. The worst egotism imported from the mindset of the US commercial mainstream is the fastest and most deeply rooted in the Macedonian political, economic, social milieux of today – and people are not even aware of how stuck they are in the wrong matrices. This is why our country is institutionally failing.

A constant topic of discussion at the festival has been the lack of suitable/affordable venues in the region. Your thoughts?

In Macedonia, the independent scene is developing rapidly and that’s great because they produce more honest and fresher theatre, but none of them owns their own working stage space. We all depend on other people’s spaces, and these are national theatres, municipal or national centres and houses of culture. It all depends on who and how they manage them and how open they are to collaborations with external teams. Some institutions lose touch with reality, and charge high sums for renting a stage space without offering you even the help of technicians. They behave as if they are a private venue or a private commercial institution, but they are national and municipal and they live off the public budget – which is the people’s money.

On the other hand, Skopje is an abundance of abandoned empty buildings, many of them industrial, like the other cities in Macedonia, but their transformation and re-adaptation is held back by a deliberate status quo. Where there is corruption and miserliness, it inhibits the natural processes of development just so a few people can live well at the expense of a broken system. It’s pointless.

What inspiration can Macedonia take from the Showcase this year?

Having seen good plays, some stronger than others, with a good evolutionary programme of the concept of a theatre showcase, the 2025 edition could include the best productions from the previous season in Macedonia – and not just Macedonian-language because we also produce Albanian- and Turkish-language theatre – or expand the perspective towards a wider regional programme for a Kosovo/Albania/Macedonia regional theatre showcase, if creative will and financial support permit!

7. Steven Leigh Morris on adaptations

Writer of White People, directed by Besim Ugzmajli, produced by Qendra Multimedia @ ArTurbina.

Not everyone at the Showcase may have been aware that you adapted an existing script for the premiere of White People for the festival. How did this come about?

I’d written a play called Lear in Tulsa about a black lesbian artistic director, recently hired to replace a retiring white artistic director at a semi-professional theatre in Tulsa, Oklahoma, rehearsing a production of King Lear, in which the outgoing artistic director was performing in his swansong role. That play included the black wife of the incoming artistic director, as well as a stage manager who is a person of colour, in addition to these three were three white characters: the outgoing artistic director, a politically progressive actress from Austin, Texas, and a local actor, semi-obsessed with White Replacement Theory.

The Kosovo Theatre Showcase director Jeton Neziraj had his own play Department of Dreams performed in Los Angeles at the City Garage, and I was invited by the theatre to moderate a post-play discussion. We got to know each other, Jeton invited to me to one of the festivals and that’s when I told him about my play. After he read it, he included it in a new play readings programme the following year. Jeton liked Lear in Tulsa and wanted to do it, but he felt that the three actors-of-colour would be extremely difficult to cast in Kosovo, so he asked if I could reframe the same story through the lens of the white characters – hence the slightly belligerent title White People. Among the benefits in our overly literal and identitarian era is that this new approach quashed any potential accusations that, as an older cis-gender male, I had no right to script a black lesbian character. The revision also tightened the story considerably.

What was the input from producers Qendra Multimedia and how was it for you to process as a playwright in tackling that cultural translation of the script?

The input was primarily dramaturgical, issues such as how to raise the stakes of the drama. This was inordinately smart and helpful. As for cultural issues, they were concerned that the play was too American to be pertinent to the Balkans. But the festival directors didn’t actually believe that, and they felt that the play had sufficient universal insights into racism and the culture wars that it was worth doing. However, they hedged their bets by adding a semi-improvised scene near the end where the characters squabble over a Roma theatre director leading a new theatre in Kosovo, and what the blowback to that would be. It fit nicely into the play’s style, and it helped my play speak to a situation on the other side of the planet.

Is a festival a good lab to do this sort of thing?

It’s such a good lab that I’m taking all the revisions I made and adapting them to the initial play, Lear in Tulsa, that’s being further developed here in LA.

And what’s the takeaway from Tirana?

There are many theatrical languages, and none of them is as provincial as one might expect. The trick is to strengthen the universal art of storytelling and remain flexible as to how that art can work an ocean away. I wrote this play on a mountain in Southern California, next thing I know it’s being translated into Albanian so that it can sail across the Atlantic Ocean and the Adriatic Sea and land on its feet in Kosovo. To me, that’s nothing short of a miracle.

8. Aktina Stathaki on translations

Director and translator of the Greek production of The Internationals, written by Jeton Neziraj and produced by Between the Seas: Mediterranean Performance Lab (Greece).

Between the Seas

Why this play?

For one I find the play to be very timely, especially in a European context, as it speaks about the birth of a nation and all the factors and parameters that make it happen. In a Europe presently ridden by nationalisms, it is important to be reminded of the artificiality in the making of nation states, their constructedness and the calculations and interests that go into it. The play juxtaposes the need to belong, the need for a people’s collective identity to be affirmed and acknowledged, but it does so not on nationalist lines but on the basis of the haves and have nots, the winners and losers of history – and that’s something that can resonate with a lot of peoples across the Balkans and beyond.

Also because it speaks a lot to the Greek reality. Not just for Greece post-crisis but for Greece as it has been historically constituted as a nation-state, a ‘bastard’ between the Balkans, Middle East and Europe, always looking up to the West to construct its identity and sense of self, historically under the influence and control of the Euro-American axis. The crisis from 2009 onwards only exacerbated some of those realities and characteristics. There is a line in the play by a person who describes the situation in the country, which says, “they cause car accidents but no one ever goes to court”. When we were performing the show in Athens, we had this tragic train crash in the area of Tempi in central Greece, where over 50 people, mostly students in their 20s were killed. The reasons for the train crash had to do with the privatisation of the train system and fatal omissions in maintenance on the part of the government. Yet no one was bought to court, no one has been held accountable for this tragedy. I think this sums up how the play resonates with us in Greece.

Beyond all this, I love how the play – written without any stage directions, characters, locales – leaves a wide open space for the director to imagine and create worlds. That certainly intrigued me as soon as I picked up the text.

How did its genesis take shape?

I first did a staging of the play back in 2019, in New York with American actresses. Thanks to a residency at the LaGuardia Performing Arts Center, I had plenty of time to test different ideas, see what works and what didn’t. So after the NYC performances I had a good first ‘draft’ of the staging. But I always wanted to stage it in Greece because I knew Greek actors and audiences would relate very differently with the material – and it was true. In Athens I kept many of the ideas and the staging I had already worked on, but we were able to dive deeper, create new material with the Greek actresses, come up with new ideas that would fit better a Greek audience. The space where we performed in Athens also shaped the piece – it is a gallery space so there were some scenes that were staged as ‘installations’.

Does The Internationals hold its own level of provocation/humour for Greece?

Absolutely, there is this Balkan reality, sarcasm and self-deprecating humour that the Greek audience can very easily grasp and relate to. And of course, as I mentioned, there are so many historical parallels and the experience of a neo-colonial present that Greek audiences understand deeply.

Was translating it a challenge?

I translated it from English. I actually enjoyed the process of translation very much because the text has a very lively rhythm , it has a lot of humour and transferring this into a Greek sensibility, making it work in a form that would be ‘actable’ was fun and, I believe, successful. A lot of audiences commented on how ‘Greek’, colloquial and accessible the text sounded to them.

Was there any input from Jeton?

We had some discussions occasionally but no there wasn’t a lot of input. I like that Jeton is very trusting, I don’t think he is overprotective with his plays so I was absolutely free to imagine and stage it as I wanted.

How does the play fit with Between the Seas?

The mission of BTS is to promote exchanges between Mediterranean countries as well as the Mediterranean and the US. Introducing new Mediterranean plays in the form of staging readings or full productions is a key part of this mission. Even if Kosovo is not on the Mediterranean per se, we always consider the Balkans as part of the broader region and we are interested in sustaining those exchanges. Our programming also has an overall socio-political direction, we are interested in works – be it in dance, photography or theatre – that engage with the world we live in.

In that sense it was important how overtly political the play is, how it speaks to a reality from a point of view that is still largely unknown – and still controversial – in Greece. Presenting underrepresented stories, voices, communities or versions of history is very central in our mission and I believe The Internationals in many ways fits into that, both as a play but also as a production – and this was the first time as far as I know that a work from Kosovo has been presented in Greece as a full production.

9. Aurela Kadriu on discussions

Curator of the Kosovo Albania Theatre Showcase 2024 and programme director at Qendra Multimedia.

qendra.org

Is it different to be programming a festival in another country?

Albania is a completely different jurisdiction and it has a completely different system of cultural institutions and institutions. But, like any festival, in terms of programming it comes down to the actual amount of shows that we have available, which we can’t really control considering that we showcase works of public theatre institutions. We are an independent company, so we don’t have control over the production policies or consistency of the institutions whose work we showcase. This year in Albania we have ten shows, last year it was 11, but in 2022 we had 14 shows because it was a very fruitful year for the independent scene in Kosovo and we could not leave them out of the programme – because not only were they good, they were also representative of the artistic quality, aesthetics and themes that we are discussing on stage.

And programming also depends on the venues available.

In Prishtina we have a very limited number of theatres: the ODA Theatre that we co-run as Kosovo’s only independent theatre, the alternative space where the National is currently working (having been closed for renovation in the first half of 2022), and the small Dodona city theatre. One reason why we had more shows in 2022 was that most of the shows produced by the independent scene actors were staged in alternative spaces: one was staged at the Ethnological Museum, another at the Lapidarium of the National Museum and another at the Prison Museum of the City of Pristina, which presents the stories of former political prisoners.

The curation also depends on the consistency of productions, and the independent scene is not that consistent (for multifaceted reasons) so you may have a lot of shows one year and then less in the the next. Here in Albania the situation was different because there are almost no shows from the independent scene that we could programme, at least no shows produced in the last year that are still running – and I mention this because it is an indicator of the existence of a country’s independent scene. There are also not very many productions from the state theatres because, as the discussion has been over the festival, theatre in Albania is one of the most under-financed scenes in the region – perhaps only surpassed by North Macedonia – and finance is what a theatre scene depends on. Of course you don’t only want to curate and programme quantity, you also want quality. The nature of the Showcase is such that the shows that we programme don’t necessarily reflect a curator’s artistic or preferred aesthetics but they should be representative of the production of the country.

So both in terms of programming and in terms of organising the Showcase in another country, it has had its challenges. We can’t make the assumption that because it’s Albania and they speak the same language, it’s going to be easy for us. It is different, and we have been working for a year on making sure that the festival will be a success.

And back to the question of venues?

One practical reason for moving our festival to Tirana is that Kosovo’s National Theatre is under renovation and we also had signals that the ODA Theatre will also enter renovation soon. We were not able to guarantee that that we were going to have sufficient spaces in Prishtina, but we knew that in Tirana we would at least have three working spaces: two in the ArTurbina Theatre and one at the Tulla Culture Centre. It’s interesting that ArTurbina is also an alternative space for the National Theatre of Albania, because the physical National Theatre in Tirana was demolished in 2019 and its replacement is still under construction.

Is there also a conceptual reason for making the move?

We have held seven editions in Kosovo, which is an Albanian-speaking theatre scene, so it made sense that we extend the Showcase. As we highlighted in a short text that we circulated before the beginning of the festival, theatre in Albania is internationally unexplored and somehow there is not even a discussion about that. So we felt it was important to spark that discussion. It helps that international communication is a mission for Qendra Multimedia, it is a political act where we communicate beyond borders by working with international artists and taking our work to other countries. We wanted to spark this in Albania too by bringing not only ourselves but also the international guests and international productions. It is important that the international guests value this, but what’s more important is that the local artists value it. We can already see that the showcase is making a difference, there is change because the discussion is out there.

The Kosovo Albania Theatre Showcase 2024 was curated by Aurela Kadriu (Qendra Multimedia), with co-curators Gjergj Prevazi (general director of the National Experimental Theatre Kujtim Spahivogli) and Altin Basha (general director of the National Theatre of Albania).